Navigating The Co-Founder Break-up: Part 2

How do you navigate a co-founder breakup to ensure your business services?

In part one, I covered assessment: reading your documents, understanding the four paths forward, and checking your motivations before making moves.

This is the execution playbook.

The goal is a clean exit. That means the departing founder leaves with fair value, the company continues operating, investors stay calm, and nobody spends the next three years in litigation. It happens more often than you'd think. But it requires discipline.

Negotiating the Buyout

Most co-founder separations end in a buyout. One side pays the other for their equity. The question is always, how much?

Start with the documents. Your stock purchase agreement or operating agreement may specify how shares are valued in a buyout scenario. Some include formula-based provisions tied to revenue multiples or book value. Others require an independent appraisal. A few are silent, which means you're negotiating from scratch.

If you're negotiating from scratch, expect a gap between what the departing founder thinks the company is worth and what the remaining founder will pay. This gap is normal. The departing founder is pricing in future potential. The remaining founder is pricing in risk and the cost of capital. Neither is wrong.

Three factors typically bridge the gap.

The first is timing. A structured payout over twelve to twenty-four months is easier to swallow than a lump sum. And it aligns incentives: the departing founder has reason to cooperate during transition if future payments depend on it.

The second is non-competes. A narrower non-compete justifies a lower price; a broader one justifies a higher price. If the departing founder wants flexibility to start something new, they may accept less cash in exchange.

The third is uncertainty. When valuation is unclear, earn-outs can work. The departing founder receives a base payment now and additional payments if the company hits milestones over the next one to three years. This is common in M&A for a reason: it allocates risk to the party best positioned to manage it.

One more thing on price. Do not anchor to the last round's valuation. Preferred stock and common stock are not the same. Investors get liquidation preferences, anti-dilution protection, and board seats. A co-founder's common shares are worth less, sometimes significantly less, especially if the company hasn't hit its milestones.

Handling Equity

Equity mechanics are where deals get complicated. Answer several questions before you can close.

What happens to unvested shares? Usually, they're forfeited. The departing founder keeps what has vested and walks away from the rest. But if the departure is negotiated rather than forced, there's often room to accelerate a portion of the unvested equity.

What about vested shares? The company or remaining founders typically have a right of first refusal, letting them buy shares at the offered price before the departing founder can sell to anyone else. Many agreements also include a call option allowing the company to repurchase vested shares at fair market value upon departure. Check your documents. The answer is almost certainly there.

How is fair market value determined? Some agreements specify a formula. Others require a third-party appraisal. If yours is silent, you'll need to negotiate a methodology. Common approaches include a multiple of trailing revenue, a discounted cash flow analysis, or an average of two independent appraisals. Pick the one that fits your business.

What about restricted stock versus options? Restricted stock is easier: the departing founder either keeps it subject to existing restrictions or sells it back. Options are more complex. Most option agreements require exercise within ninety days of departure or they expire. If the departing founder can't afford to exercise, this becomes a sticking point. Some deals include an extended exercise window.

Finally, update the cap table. I've seen companies skip this step and discover years later, during a financing or sale, that their records don't match reality. A clean cap table is worth the hour it takes to fix.

Handling Intellectual Property

IP is the other place where co-founder separations get messy.

Who owns what the departing founder built?

If you have a proper PIIA (Proprietary Information and Inventions Assignment agreement), this is easy. Everything the founder created during employment belongs to the company. The departing founder confirms this in the separation agreement and moves on.

If you don't have a PIIA, or if it's ambiguous, you have a problem. In some states, employees own the IP they create unless there's an express assignment. In others, it depends on whether the work was within the scope of employment. You'll need to negotiate an explicit assignment.

A few specific things to address.

Code and technical assets. The departing founder should confirm that all code, designs, and technical documentation have been transferred and that they haven't retained copies. This includes personal repositories, cloud storage accounts, and devices.

Trade secrets and confidential information. The separation agreement should include robust confidentiality provisions covering customer lists, pricing, strategy, and anything else that gives the company a competitive advantage.

Non-solicitation. Most separation agreements prohibit the departing founder from soliciting employees and customers for a defined period, usually one to two years. This is enforceable in most states even when non-competes are not.

Non-disparagement. Both sides agree not to say anything negative about the other. This is harder to enforce than it sounds, but it sets expectations.

Managing Investors

Investors hate surprises. A co-founder departure is a surprise. Your job is to make it a manageable one.

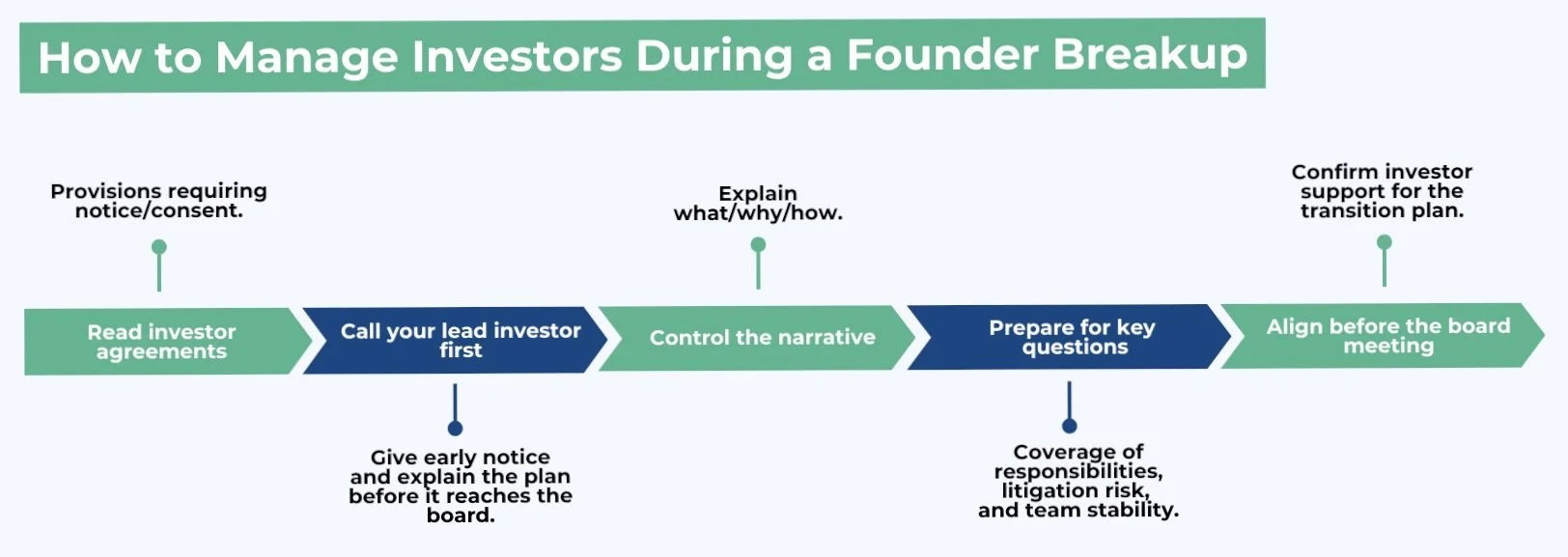

Start with your investor agreements. Many contain provisions requiring notice or consent for changes in key personnel, equity transfers, or material corporate events. A co-founder departure may trigger one or more of these. Read the documents before you have the conversation.

Then have the conversation. Call your lead investor before anything becomes public. Explain what's happening, why, and what the plan is. Be direct. Investors know co-founder departures happen. What they're assessing is whether the remaining team can execute and whether the departure signals deeper problems.

Frame the narrative. A voluntary departure where founders had different visions is very different from a termination for cause or a blowup. Control the story before someone else does.

Anticipate questions. Investors will want to know how the departing founder's responsibilities will be covered, whether the separation is amicable, whether there's litigation risk, and whether key relationships are affected. Have answers.

Get alignment before the board meeting. If your investors are on your side before the meeting, the meeting is a formality. If they're not, you have a problem that goes beyond the co-founder separation.

Investors fear surprises. Align early so the board meeting becomes a formality.

Documenting the Exit

The separation agreement is the final product. It should be comprehensive enough to prevent future disputes but not so complex that it takes three months to negotiate.

At minimum, the agreement should cover:

Equity treatment. What happens to vested and unvested shares? At what price is the buyout happening? What's the payment schedule?

Role and transition. When does the departing founder's employment or officer status end? What are their responsibilities during the transition period? Will they remain on the board, and if so, for how long?

IP assignment and confidentiality. Explicit confirmation that all IP belongs to the company. Robust confidentiality provisions. Return of company property.

Restrictive covenants. Non-compete, non-solicitation of employees, non-solicitation of customers, and non-disparagement. Define the scope, geography, and duration.

Mutual release. Both sides release each other from claims arising out of the co-founder relationship. Carve out any ongoing obligations under the separation agreement itself.

Representations and warranties. The departing founder confirms they have no undisclosed claims, haven't taken company property, and will cooperate with future legal matters. The company confirms the buyout price reflects all amounts owed.

Dispute resolution. Specify whether disputes go to arbitration or litigation, and in which forum.

This is not a document to draft yourself. Get a lawyer involved. A few thousand dollars now prevents a few hundred thousand in litigation later.

A clear separation agreement prevents future disputes and protects both founders.

For Remaining Founders

If you're the one staying, your job isn't just to manage the departure. It's to keep the company running while it's happening. That means staying focused on the business, even when the separation is consuming your attention.

Assign someone, ideally not you, to manage the transition logistics. You need to be present for the key conversations and decisions, but you don't need to be the one updating the cap table.

Communicate clearly with employees. They will notice something is happening. Silence breeds speculation, and speculation is rarely better than the truth. Once the separation is finalized, tell the team what they need to know: the departing founder is leaving, the company is in good shape, and here's what changes.

Document the departing founder's knowledge. Before they leave, capture everything they know that isn't written down. Customer relationships, technical decisions, vendor contacts, and institutional history. Schedule working sessions if you have to. Once they're gone, you can't get this back.

And finally, take care of yourself. Co-founder breakups are emotionally draining, even the amicable ones. You're losing someone you built something with. That matters. Don't pretend it doesn't.

For Departing Founders

If you're the one leaving, your goal is to exit cleanly with fair value and without burning bridges.

Be professional. Even if the relationship has deteriorated, act like someone is watching. Your reputation in the startup community is an asset. Don't trade it for the satisfaction of venting.

Negotiate for what matters to you. If you want flexibility to start something new, push for a narrow non-compete. If you want certainty, push for cash at closing rather than earn-outs. Know your priorities before negotiating.

Get independent legal advice. The company's lawyer represents the company, not you. Even if you trust them, you need someone looking out for your interests.

Don't sign under pressure. A few extra days to review the documents is reasonable. If the other side won't give you time to review, that tells you something.

And once it's done, move on. Starting something new is almost always more valuable than relitigating the past.

The Bottom Line

Co-founder separations are hard. They're emotionally charged, legally complex, and high-stakes for everyone involved.

But they're also survivable. The founders who navigate them successfully share a few things in common: they move deliberately, they separate emotion from economics, and they get the right help at the right time.

If you're facing a co-founder breakup, take it seriously. Not as a personal failure, but as a business problem with a business solution. Get your documents in order, understand your options, and execute.

The company you're building is worth protecting. So is your next chapter.