Minimum Viable Compliance: Essential Legal Requirements for Early Stage Startups

The legal work you skip today becomes the fire drill you pay triple for tomorrow.

I have watched promising startups bleed cash and credibility fixing compliance gaps that could have been handled for a fraction of the cost at formation. The co-founder agreement you never signed. The contractor you misclassified. The 83(b) election you filed late (or not at all). These are not edge cases. They are the hits parade of startup legal failures.

This post is a reference guide. Bookmark it, forward it to your co-founder, revisit it quarterly. The goal is not to turn you into a compliance officer but to help you understand what you actually need to do, why, and when you can get away with doing less.

What "Minimum Viable Compliance" Actually Means

An MVP gets something functional into users' hands so you can iterate based on real feedback. Minimum viable compliance works the same way: establish the legal foundation that keeps you out of trouble now, positions you for growth, and gives future investors confidence you have not created a mess for them to inherit.

This is not about checking every box from day one. It is about knowing which boxes matter most at your stage.

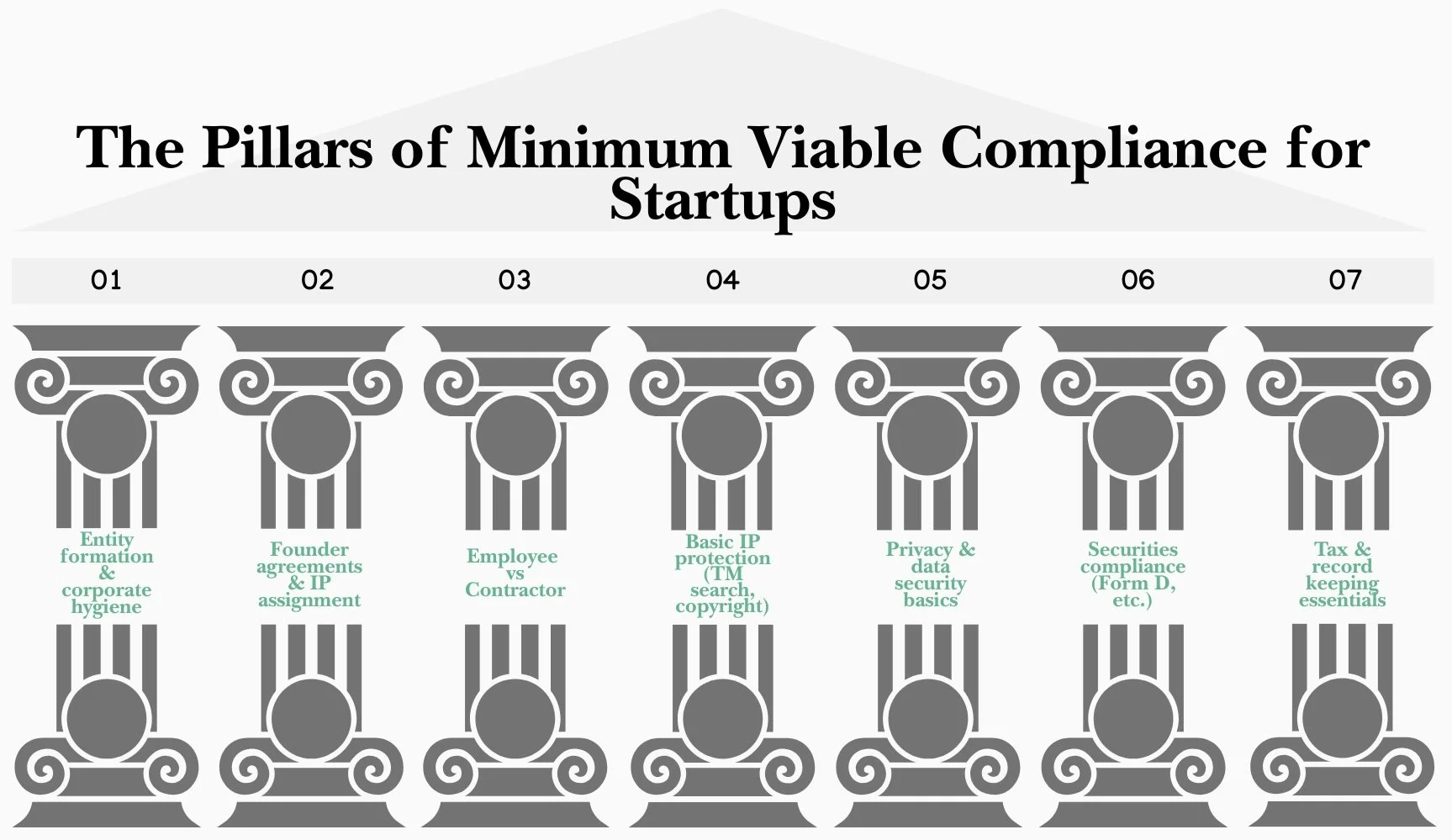

The essential legal foundations every early-stage startup must put in place.

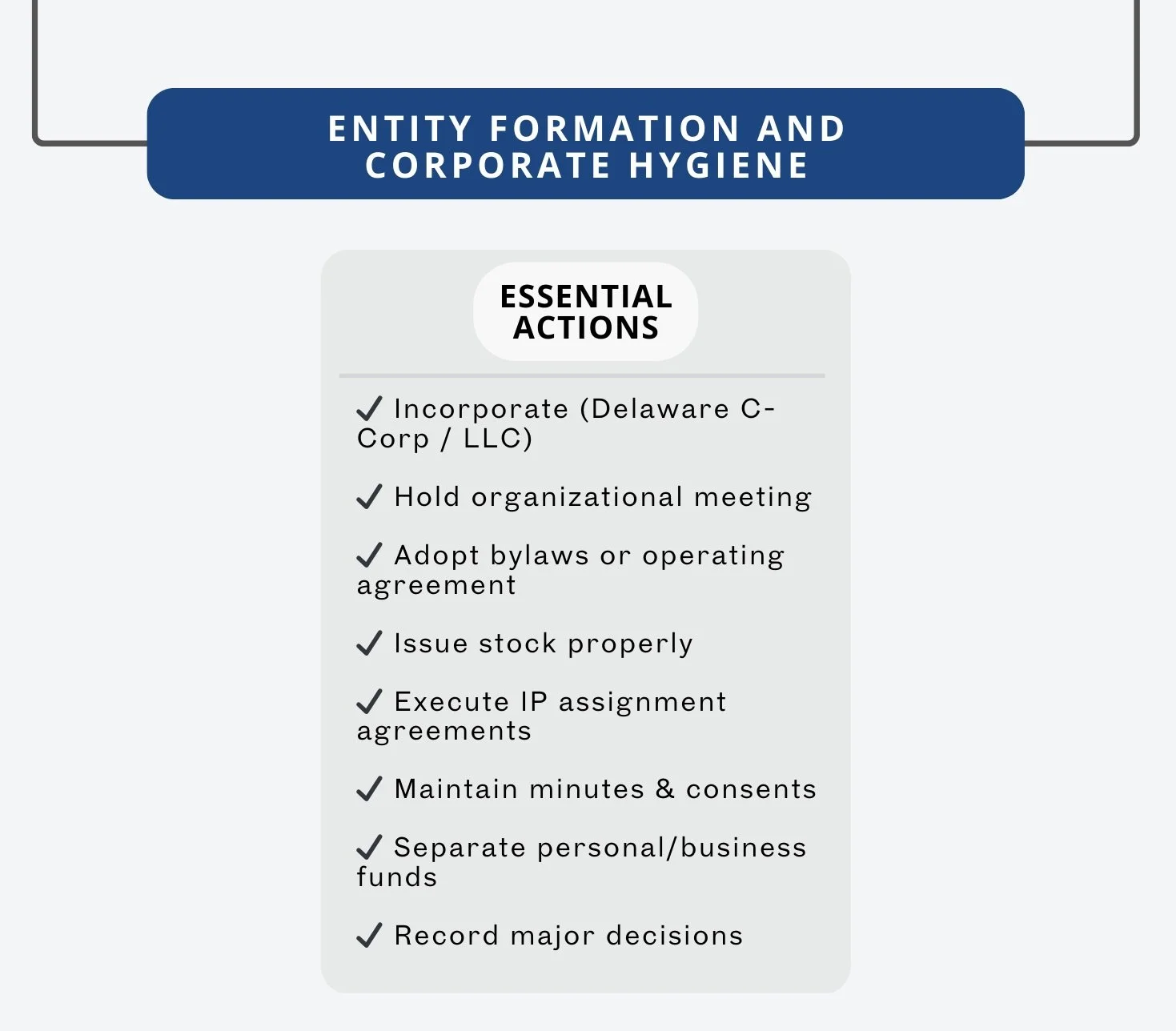

Entity Formation and Corporate Hygiene

Most startups raising venture capital should incorporate as Delaware C-corporations. Delaware's corporate law is well-developed, predictable, and familiar to investors. You can operate anywhere while incorporated there.

If you are not planning to raise institutional money, an LLC may make more sense depending on your tax situation. Talk to an accountant before deciding.

Either way, follow through on the formalities. Hold an organizational meeting (even if it is just you signing a written consent), adopt bylaws or an operating agreement, issue stock properly, and keep records of board and shareholder actions. Most founders treat these as annoying paperwork. They are. But failing to maintain proper corporate records creates "piercing the corporate veil" risk, meaning a court can hold you personally liable for business debts.

The practical takeaway: once you form an entity, act like it exists. Do not commingle personal and business funds. Document major decisions. Keep a minute book.

Proper corporate hygiene protects founders from personal liability and future investor issues.

Founder Agreements

I have written about this before, and I will keep writing about it: document your co-founder relationship in writing before you build anything meaningful together.

A founders' agreement should address, at minimum, the equity split and vesting schedule, what happens if a founder leaves, decision-making authority, intellectual property assignment, and non-compete obligations.

Vesting deserves special attention. If you and your co-founder each take 50% on day one, fully vested, and your co-founder leaves six months later for a job at Google, they still own half your company. Standard four-year vesting with a one-year cliff exists precisely to prevent this. You do not need a lawyer to understand why that matters.

For intellectual property, every founder should execute an invention assignment agreement confirming that anything created for the company belongs to the company. Investors will ask about this during due diligence, and the absence of clear IP assignment creates real problems.

Employment and Contractor Classification

Misclassifying workers is one of the most common and expensive compliance failures at early-stage startups.

Employees get wage and hour protections, unemployment insurance, workers' compensation, and certain tax withholdings. Independent contractors do not. Calling someone a "1099 contractor" does not make them one. What matters is the nature of the relationship: how much control you exercise, whether they work exclusively for you, whether they set their own hours.

California's AB5 and similar laws have made this even more stringent. Getting it wrong exposes you to back taxes, penalties, and lawsuits. The IRS is not sympathetic to startups that plead ignorance.

For employees, even at the earliest stages, you need to comply with wage and hour laws: minimum wage, overtime for non-exempt employees, accurate time records, proper pay frequency. You also need Form I-9 verification and compliance with anti-discrimination laws.

If you hire in California, New York, or similar jurisdictions, the requirements multiply. Consult a lawyer or use a reputable HR platform before making your first hire in an unfamiliar state.

Intellectual Property Protection

At the early stage, it is understandable to not have a comprehensive IP strategy. But certain fundamentals should be in place.

First, make sure your company actually owns what it is building. The work-for-hire doctrine does not automatically assign all contractor work to you; you need a written agreement with co-founders, employees, and any contractors who contribute to your technology

Second, do basic trademark clearance before committing to a brand name. Search the USPTO database and Google to confirm nobody else is using your name in a related industry. Rebranding after you have built recognition can be painfully expensive.

Third, if you have genuinely novel technology, consider whether a provisional patent application makes sense. A provisional buys you 12 months of "patent pending" status at relatively low cost while you validate your market.

Copyright protection for code and content arises automatically, but registering with the Copyright Office before infringement gives you access to statutory damages and attorney's fees, which dramatically improves your litigation posture.

Data Privacy and Security

If your business collects personal information from users, customers, or employees, you have compliance obligations.

At the federal level, baseline requirements are modest for most startups, but sector-specific rules apply for health information (HIPAA), financial data (GLBA), and children's data (COPPA).

State law is where things get complicated. California's CCPA and CPRA impose significant obligations on businesses meeting certain revenue or data-volume thresholds, even if the business is not based in California. If you have California customers, you probably need a privacy policy disclosing what data you collect, why, and how users can request deletion.

Beyond legal compliance, security practices matter because a breach destroys customer trust faster than any other operational failure. Encrypt data in transit and at rest, limit access to sensitive information, and have an incident response plan. You do not need a CISO on day one, but do not store passwords in plaintext or share AWS credentials on Slack.

Securities Law Compliance

If you are raising money from investors, you are selling securities, and securities sales are regulated.

Most early-stage startups rely on Regulation D exemptions. The most common for seed and Series A rounds is Rule 506(b), allowing unlimited fundraising from accredited investors without general solicitation. SAFE notes and convertible notes are securities too, even though they feel less formal than a priced round.

Every securities issuance requires a Form D filing with the SEC within 15 days of the first sale, plus state "blue sky" filings in relevant jurisdictions. Most startups outsource this to their lawyers, but you should know it exists.

Equity crowdfunding under Regulation Crowdfunding is an option for smaller raises (up to $5 million in 12 months), but it comes with its own disclosure requirements. It can work for consumer-facing businesses with an engaged community; it is rarely right for enterprise B2B startups.

Tax Filings and Record-Keeping

Tax obligations start the moment you form an entity. At minimum: obtain an EIN, file annual federal income tax returns, and comply with state franchise tax requirements.

Delaware imposes an annual franchise tax on corporations. The default calculation produces absurdly high bills for startups with lots of authorized but unissued shares; use the "assumed par value capital" method instead.

If you have employees, withhold and remit payroll taxes, file quarterly employment tax returns (Form 941), and furnish W-2s and 1099s by applicable deadlines.

Startups often underestimate payroll tax compliance because they use payroll services that handle most mechanics automatically. That is fine until something goes wrong. The IRS takes payroll tax failures personally. The trust fund recovery penalty can make officers and directors personally liable for unpaid payroll taxes.

Industry-Specific Regulations

Depending on what you are building, additional requirements may apply.

Fintech startups need to consider money transmission licensing and consumer lending regulations. Healthcare startups need HIPAA compliance and potentially FDA approval. Alcohol, cannabis, and firearms each have dense regulatory frameworks. AdTech faces an evolving patchwork of privacy rules and platform restrictions.

The specific requirements vary widely. The point is to recognize early whether your business operates in a regulated industry and factor compliance costs into your planning. Do not build first and ask regulatory questions later.

Practical Takeaways

For founders: compliance is not glamorous, but neither is lower back pain. Address the basics early. Know what you are deferring and why. When in doubt, spend the money on competent legal advice rather than learning by expensive mistake.

For lawyers advising startups: resist the urge to perfect every document. Your client needs a solid foundation, not an ironclad fortress. Identify the highest-risk areas, address those thoroughly, and provide a clear roadmap for what comes next.

For accelerators and founder programs: incorporate basic legal hygiene into your curriculum. Founders should not learn about 83(b) elections six months too late or discover worker misclassification issues when trying to close a round.