What Every Founder Should Know About Trade Secrets

A trade secret is business information that has value because competitors do not know it. It covers practical know-how that remains confidential. Examples include unreleased source code, pricing formulas, supplier lists with negotiated terms, training datasets, manufacturing steps, and launch plans with dates and partners.

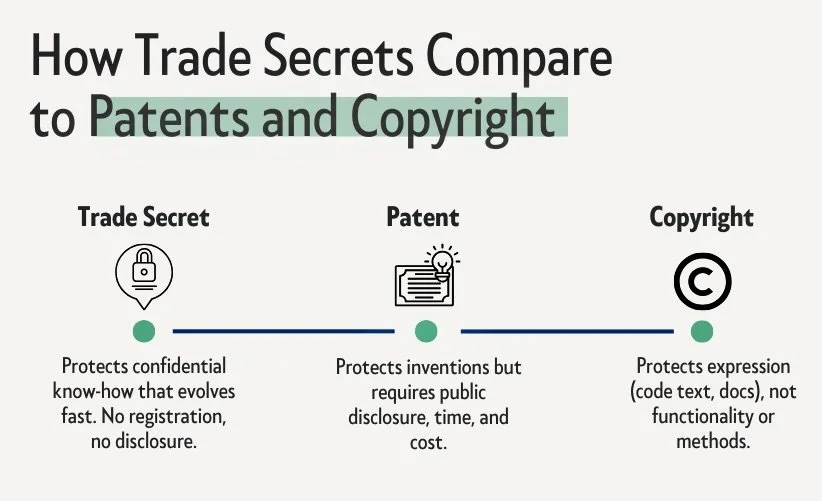

Trade Secret vs Patent or Copyright

Young companies compete on speed and accumulated know-how. Patents are slow. They require novelty and nonobviousness, careful drafting, and prosecution that can take years. Applications are published about eighteen months after filing, which means you disclose your method long before you receive enforceable rights. If the product pivots during that window, the claims you pursued can miss the mark. Patents also come with real cost, filing and prosecution fees, inventor time, and later maintenance.

Copyright protects expression rather than method. It covers the specific text of source code, design files, and documents. It does not protect the underlying functionality, data structures, or processes. A competitor can reimplement features in new code and remain outside your copyright. Facts in a dataset are not protected. These limits matter when your advantage lives in process knowledge, tuning, or integration choices.

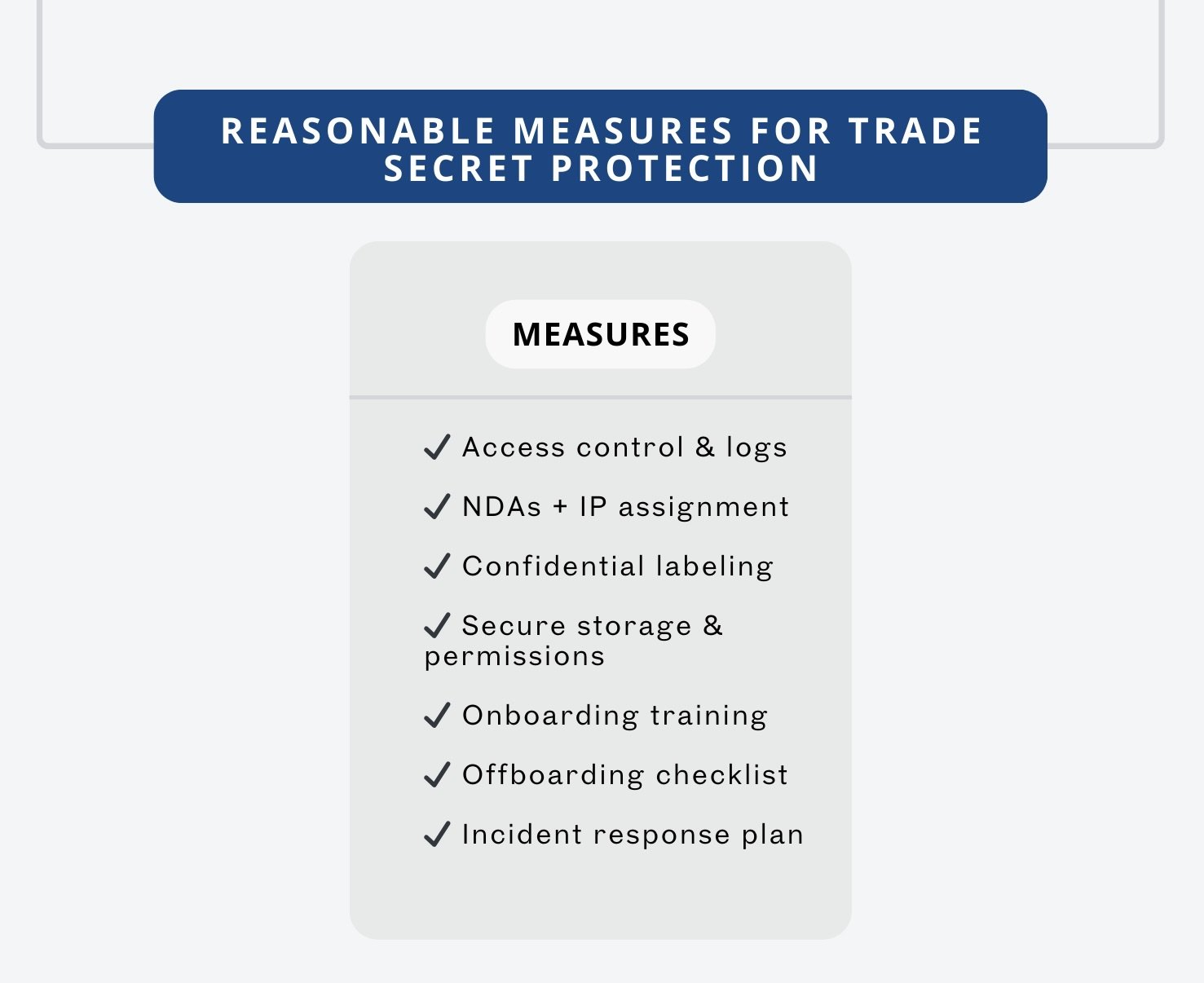

Trade secret protection fills this gap by protecting practical know-how that changes as you iterate without public disclosure. To qualify as a trade secret under federal law, the Defend Trade Secrets Act, and most state laws, the information must have economic value from not being generally known, and you must take “reasonable measures” to keep it secret. Reasonable measures means concrete steps you can show later, access controls and logs, NDAs and IP assignment in your agreements, consistent labeling and storage, onboarding and refresher training, and clean offboarding. When those elements are in place, you have a legal path to stop misuse and seek remedies.

Know what each protects—and what it doesn’t.

What “Reasonable measures” Means Practically

Courts expect a system that you can describe and prove. Start with access control. Grant only the access each role needs, use groups rather than one-off permissions, disable accounts the day someone leaves, and keep logs.

Label and store information consistently. Mark sensitive documents “Confidential,” keep them in systems that record who viewed or downloaded them, and separate proprietary code from open source with a clear folder structure.

Train team members on confidentiality as part of onboarding. Explain what the company treats as confidential using examples from your stack. Set simple rules for cloud tools and personal devices. Record attendance so you can show the training happened.

Handle departures with a checklist. Collect devices, disable accounts, and retrieve or wipe shared folders. Give the departing person a short memo that confirms continuing confidentiality duties.

Plan for incidents before they occur. Assign an owner, define first-day steps, preserve logs, and involve counsel early. Speed and documentation determine whether you can prove what happened.

If you can show this level of care with policies, logs, and signoffs, you are likely to satisfy the “reasonable measures” requirement.

Protection only works when you can show the steps you took.

Draft to Maximize Protection

Put confidentiality in writing. Use NDAs for employees, contractors, and partners. Add confidentiality and IP assignment to offer letters, advisor letters, and vendor agreements. State plainly that trade secrets belong to the company.

Your inventions and IP assignment agreement should expressly cover trade secrets and confidential information. Include a carve-out for general skills and knowledge so careers remain portable, paired with a strict prohibition on bringing in third-party secrets. In handbooks and security policies, list concrete examples of company confidential information so no one has to guess. In investor updates and board decks, avoid publishing details that would convert secrets into general knowledge.

Where trade secrets do not fit

Secrecy fails when the product reveals the method to any competent observer. If customers can reverse engineer your approach from what you ship, trade secret protection will be thin. If publication is part of your strategy, for example academic work or detailed marketing papers, expect protection to narrow. Many teams use a mix. Patent the inventions that meet the test and matter to your moat. Keep surrounding process knowledge confidential.

Common failure points and how to fix them

Unmanaged SaaS spreads sensitive data. Teams spin up tools with default sharing and files land in personal drives. Fix this with a lightweight app inventory and a simple procurement gate.

Open-source licensing creates surprises. A developer pulls code under a license that requires disclosure, then the team treats the module as secret. Fix this with a basic license review and an allowlist.

Partner conversations leak when terms are loose. Someone emails a prelaunch deck to a prospective distributor without an NDA. Fix this with a standard mutual NDA and a reflex to use it.

Hiring can import risk. A new engineer arrives from a competitor carrying “reference” materials. Fix this with clean-room onboarding and an explicit ban on bringing third-party secrets into your environment.

Advisors and contractors

External contributors often see sensitive plans. Use an advisor letter that sets grant size, vesting for any equity, confidentiality, IP assignment for work product, and access boundaries such as read-only data rooms. For contractors, use a master services agreement with confidentiality, IP assignment, and tool restrictions. If a contractor uses subcontractors, flow the obligations down.

How to act when something goes wrong

An effective response is fast and documented. Secure accounts, preserve logs, and interview with counsel present. If the facts support it, send a demand that identifies the information at a reasonable level of detail and the duties breached. When risk is ongoing, seek an injunction. Courts look for clarity on four questions: what the secret is, who had access, what protections were in place, and how misuse occurred.