The Co-Founder Breakup, Part One: Understanding Your Options Before You Act

Every co-founder relationship begins with optimism. Shared vision, complementary skills, late nights fueled by conviction that you're building something that matters. Nobody thinks about the exit when they're drafting the pitch deck.

Then something changes. The vision diverges. The workload imbalances. Trust erodes. And suddenly you're sitting across from someone you once considered family, trying to figure out how to unwind a business relationship without destroying the business itself.

I've guided dozens of founders through this process. The ones who come out intact share a few things in common: they moved deliberately, they separated emotion from economics, and they had a plan.

This is part one of that plan: understanding what you're facing and what options you have. Part two covers execution.

Why Co-Founder Breakups Are So Hard

A co-founder separation has all the emotional intensity of a divorce with all the financial complexity of an M&A transaction. You're unwinding a relationship built on trust while negotiating asset division with someone you may no longer trust at all.

The stakes are high. Get it wrong, and you can blow up the company, trigger investor panic, lose key employees, or end up in litigation that drains resources for years. Get it right, and one founder exits cleanly while the other continues building. Sometimes the company emerges stronger.

The difference between those outcomes usually isn't the underlying facts. It's how the separation is handled.

Before You Do Anything: Assess the Situation

When a co-founder relationship starts to fracture, the instinct is to act. Confront the problem. Force a resolution. Have the difficult conversation.

Resist that instinct until you've done your homework. In a divorce, you wouldn't negotiate custody without knowing what the prenup says. Same principle here.

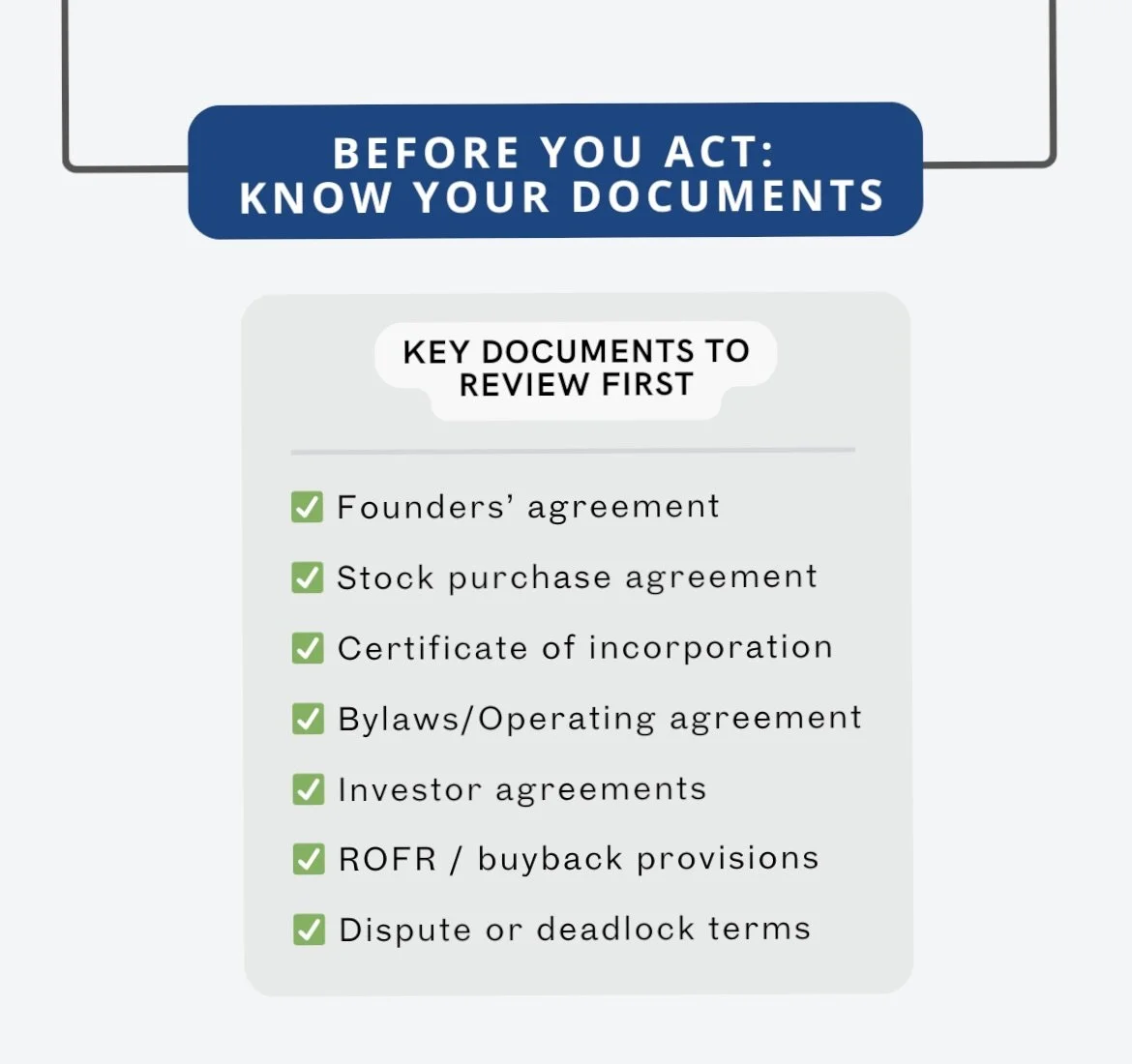

Start with the documents. Pull your founders' agreement, stock purchase agreements, any vesting schedules, the company's certificate of incorporation, bylaws or operating agreement, and any investor agreements. Read them carefully. The answers to most of your questions are in there, and you need to know what they say before you negotiate.

Most answers are already in your documents. Read them before you negotiate.

Key questions to answer: What does each founder own, and how much is vested? Are there any acceleration provisions triggered by departure or termination? What do the governing documents say about transfers, buybacks, and restrictions on shares? Does the company or do other founders have a right of first refusal? Are there any provisions addressing founder disputes or deadlock? What do investor agreements require in terms of notice or consent?

Then assess the practical realities. Who does what in the company? What happens to those functions if one founder leaves? Are there key relationships, clients, or institutional knowledge that live exclusively with one founder? What's the company's cash position, and can it afford a buyout?

Finally, check your own motivations. Are you trying to solve a problem or win a fight? The answer matters, because it will shape every decision that follows.

The Four Paths Forward

Co-founder separations generally follow one of four paths. Think of them as settlement options in a divorce, ranging from amicable to nuclear.

Path one: Voluntary departure with equity retention. The departing founder leaves but keeps some or all of their vested equity. This works when the separation is amicable, the departing founder's contribution was real, and the remaining founder and investors are comfortable with a passive shareholder on the cap table. It's the simplest path, but it requires trust that the departing founder won't create problems later.

Path two: Buyout. The company or remaining founders purchase the departing founder's equity. This creates a clean break but requires cash or a structured payment arrangement. Buyouts are common when the separation is less amicable or when having a former co-founder on the cap table creates complications for fundraising or sale.

Path three: Forced departure. The departing founder is terminated for cause, and unvested shares are forfeited. Vested shares may be subject to repurchase at a reduced price depending on the agreements. This is the most contentious path and often leads to disputes about whether cause existed and what the founder is owed.

Path four: Company dissolution. When the founders can't agree on who leaves and can't work together, sometimes the only option is to wind down the company and divide the assets. This is the nuclear option. It destroys value and should be avoided if possible, but sometimes it's the only way out of a true deadlock.

Most separations end up somewhere between paths one and two, with negotiation determining the exact terms. The goal is to find an exit that both parties can live with, not one that feels like total victory. In divorce and in business, total victory usually means everyone lost.

What Comes Next

Once you've assessed your situation and identified your path, the real work begins: negotiating the buyout, handling equity and IP, managing investors, and documenting the exit.

That's part two.

For now, the takeaway is simple: slow down, know your documents, and understand your options before you act. The founders who navigate breakups successfully aren't the ones who move fastest. They're the ones who move deliberately.